When I sent my 86-year old father my photos from Burning Man, he replied that he didn't understand: Wasn't it for "hippie kids"? What was I doing there, and what did the experience do for me?

The Love Bus (photo by Zai Divecha)

The Burn is famously different for each participant. Some Burners go to strut and party, some to share their art, a few to network and get ahead. Approaching our 60s, my husband and I get the most pleasure from camping there with our 20-something kids who extended an open invitation for the second time. But I also go to stay fresh, keep up on emerging ideas, and to prevent the fixed mindset I fear might creep in with age.

Like everyone, I bring my own kaleidoscopic lens to the playa. In my everyday life as a developmental psychologist, I experience much of my social world through a chronological telescope: When I look at children, I see the adults they may become; when I meet adults, I see the children they likely were. I’m keenly aware that we are all developing, all the time.

And I recognize that we are not nailed uniformly to a single rung on some developmental ladder. While some parts of us are reasonably established in adulthood, some parts of us remain deep in childhood. Psychologists call this normal developmental unevenness décalage, a French word that translates to “lag” or “gap.” Many people are not stuck but move flexibly and adaptively—like various spiritual teachers I’ve encountered, whose equanimity is spacious and evolved, yet who can erupt with the laughter and delight of young children.

My headdress (photo by Zai Divecha)

At home, preparing for Burning Man, I gave myself permission to go the craft table and the dress-up corner to immerse myself in the elixir of creativity and make-believe. I emerged wearing a homemade caftan, wooden necklaces, and a medieval horned headpiece, along with a second headpiece of papier-mâché branches sprouting from a drywall skullcap anchored inside a turban. By the time I hopped on my bike at the edge of the playa, I could see my 10-year-old self in the mirror.

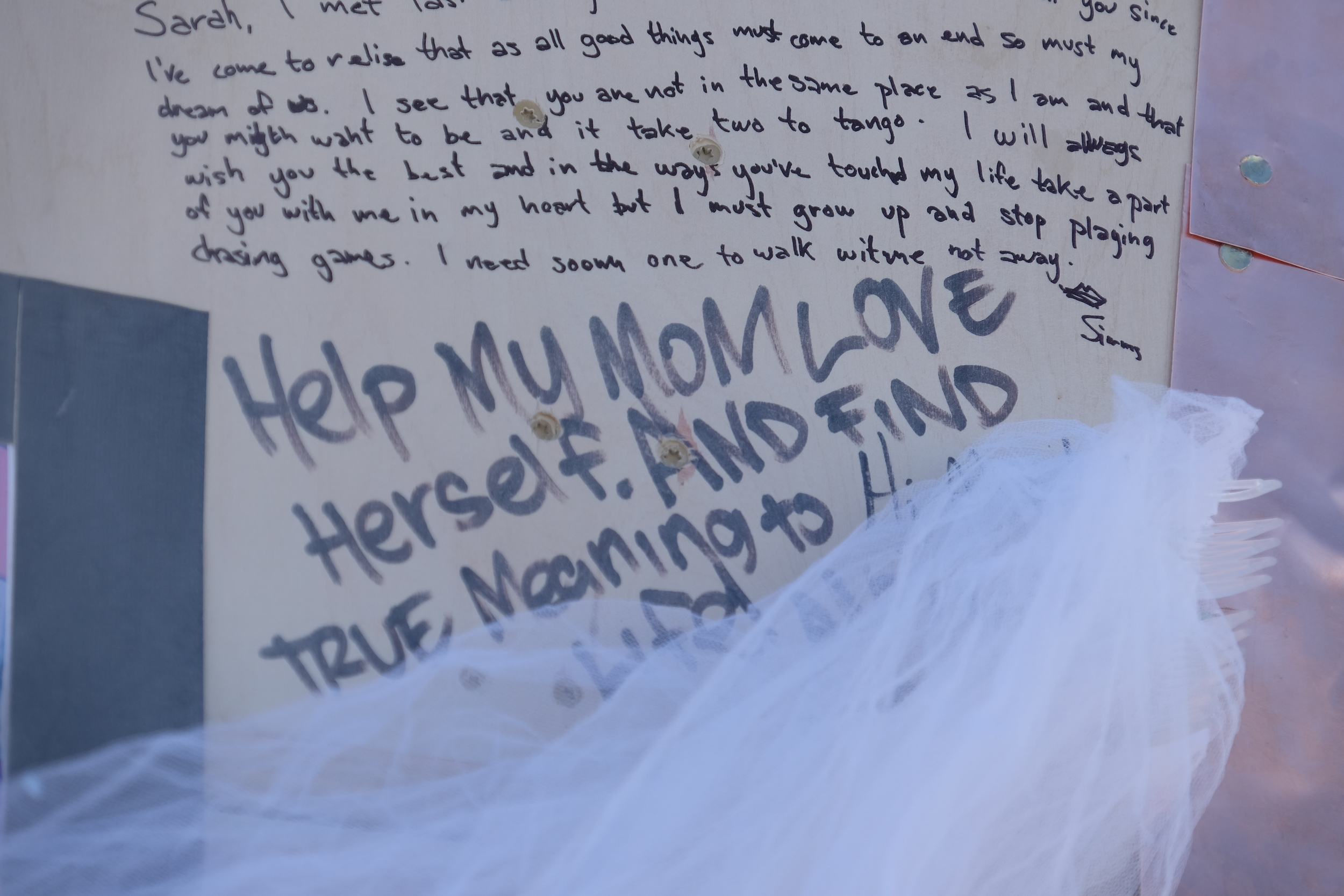

In my adult life, I advocate for improving childhood through my research, speaking, and writing. And there's much to do. In the first twenty years of life, we find out how the world works and we wrangle a place in it. For some, the process is kind, and for others it is bumpy yet manageable. For a surprising number, though, it is a tortured and traumatic path and they are deposited at the door of adulthood with handicaps and scar tissue. In a famous study of over 17,000 adults, about a third said their childhoods were free of “adverse childhood experiences” (one of ten serious conditions that can derail a child’s life), but about a quarter reported three or more types of traumas— a number that science now links to emotional and physical problems that persist well into adulthood.

And in a Hansel-and-Gretel world, the places meant to shelter, nurture, and protect children are the ones that do the most damage. Many children are traumatized in their homes, and show up at school unable to concentrate or manage their strong feelings. They are frequently misdiagnosed, drugged, punished or expelled. When adults have emotional problems, they are treated as mental health concerns, but when children have emotional struggles, they are often "behavior problems" to be controlled. Schools, too, can be unsafe: Punishment is a popular but harmful approach to managing children, while cultivating kind, emotionally supportive school cultures is effective but slow to catch on. About a quarter of kids are bullied or harassed at school--an experience that can undermine the rest of their lives. Children do not enjoy the same relationship rights that adults are privileged with; they're made to return, day after day, to the places and people who abuse them.

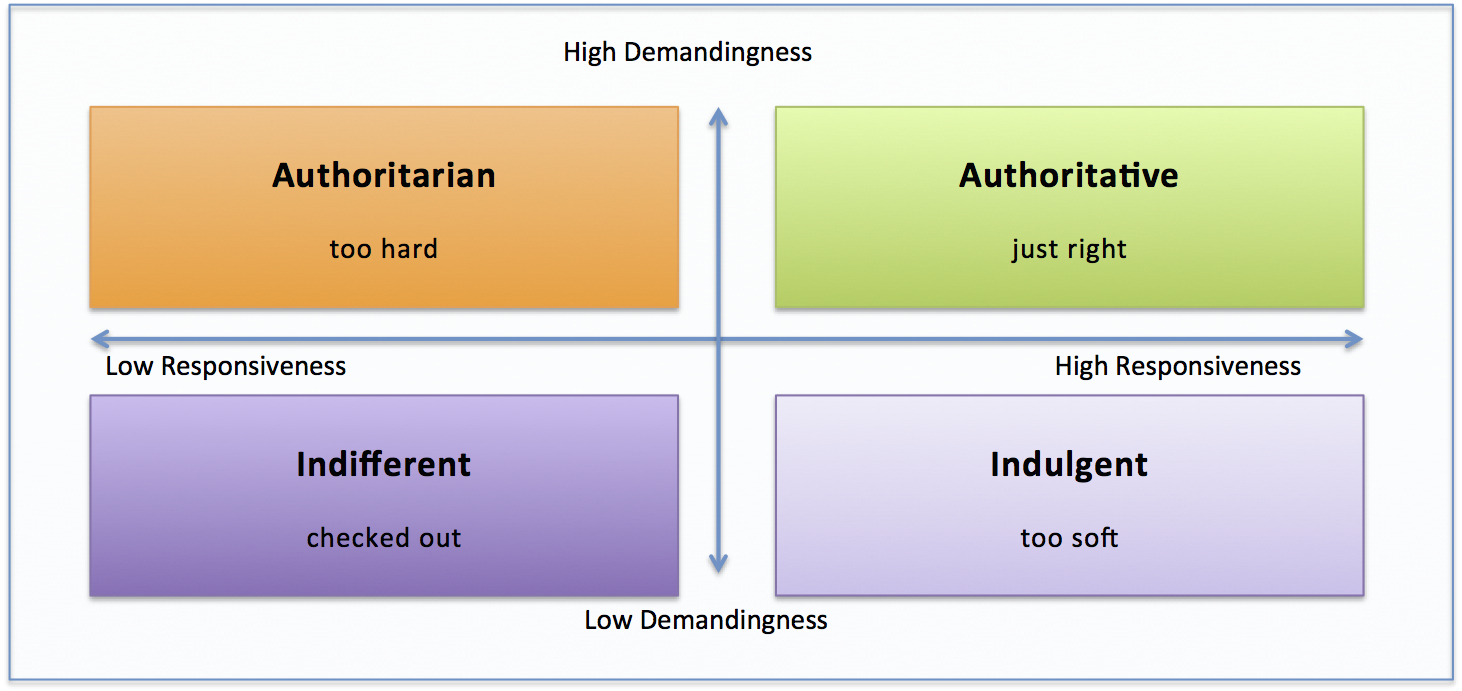

Burners are a well-educated, modestly financially secure group, but emotional difficulties are equal opportunity. The playa is sometimes described as a kind of playground, but through my eyes it is unlike the one of our childhoods. This one acknowledges some real developmental concerns. Through installations, workshops, and talks, Burning Man offers a chance for some re-dos. Some rewiring.

And it can start with letting go of some of the grief collected on the journey so far. The Temple of Promise, a stunning Gothic cornucopia rising 97 feet above the playa—is a paean to both the normal and the outsized suffering of being human.

Temple of Promise (photos by Diana and Arjun Divecha)

Visitors walk through its increasingly narrowing form, leaving baggage, burdens, pains, fears, and mementos to be burned away at the end of the week. Messages fill and are hung from every available surface, and this year someone left three small suitcases. One woman vented an angry diatribe of suffering at the hands of an abusive stepfather and a complicit mother. Another message was written to parents who had died in a plane accident: “I have not been in a small plane since yours was taken down,” it said. “A friend has offered to fly me over this temple, and I am going to try to overcome my fear. My love is eternal.” On our fourth walk through the temple, my husband quietly released some of the sorrow of losing his mother three months ago.

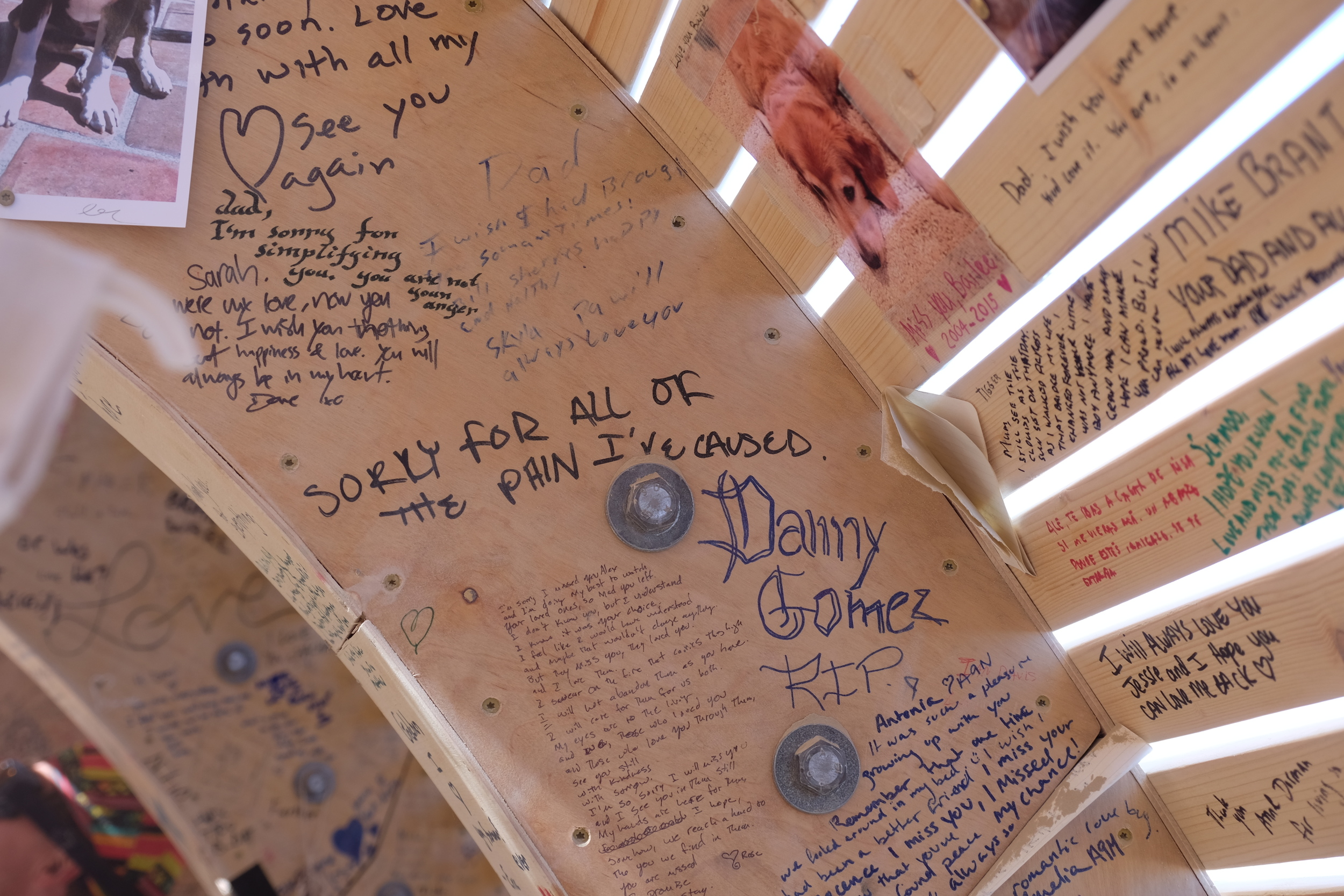

Reflect (photo by Diana Divecha)

A giant 20-by-40-foot colored tear drop, called Reflect, was captured at the point where it hits water, to represent all the tears shed by those left behind when someone takes his or her own life.

In childhood, adult power hierarchies—based on social status, gender, ethnicity, even height and attractiveness—are replicated inside the school walls, and kids learn early who’s on top and who’s pushed to the exit ramps. Kids often punish each other for being different, and power structures like schools and other institutions use whatever behavioral control possible to keep kids “in line.”

A 50-foot chapel called the Totem of Confessions contained dioramas of surreal and dreamlike black-and-white photos, oddities that might pop up from the subconscious into dreams or fantasies or fears, and that would likely be considered shameful by others. And as a reminder of ever-present judgment, there was a confessional in the interior of the chapel.

Totem of Confessions (photos by Diana Divecha)

Time Out Corner (photo by Diana Divecha)

A Time Out Corner appeared out of nowhere on the playa, recalling the frequent punishment—deserved or not—of our childhood transgressions. Timeouts for children are now understood to be ineffective, even harmful. Brain imaging studies show they light up the same neural pathways as physical pain.

Some days, after writing about bullying and trauma, I marvel that most of us make it to adulthood as well as we do. The striving to connect, to still try, to be able to still wonder, was manifest in the sculpture Love. There, two massive wire adult forms were seated back-to-back, heads down in withdrawal, while the glowing child inside each of them reached out for the other, touching hands.

Love (photo by Diana Divecha)

Identity Awareness (photo by Diana Divecha)

At Burning Man, there is an invitation to sort out what is personal encumbrance and artifice, from what authentically belongs to us. A giant question mark, barely propped up by a human figure reminded us to question the source of our choices, the source of our identity.

One of the Ten Guiding Principles of Burning Man—radical self-expression—is a direct antidote to the censoring—and censuring—of growing up, making space to question the conventions we take for granted. We took part with our crazy clothes, our go-with-the-flow schedules (some of us got up before dawn when others were just going to bed), and our explorations of new topics (from beekeeping to twerking). We passed the “Dick Parade” where 150 men bicycled through camp, bottomless, while gentle hecklers (a thing) encouraged the liberal use of sunscreen. In its counterpart, women paraded topless in "Critical Tits." Overhead, a man flew a glider, naked. “You’re guaranteed to not be the weirdest kid in the classroom,” the online guide soothes. It would be easy to dismiss the naked experimentation as exhibitionism, but I'm sure some riders may have been struggling with their body image or health concerns; for some it may have been a healing process from being bullied, targeted, or abused; and perhaps others simply wanted to walk through the wall of a conventional boundary. There are as many possible reasons as there were riders.

(Photos by Arjun and Zai Divecha)

(Photo by Diana Divecha)

But by radical, they mean deep, not crazy: Consent is the cornerstone of a civil community, the Burning Man literature reads. It doesn’t refer to just sexual and physical touch, but anything that “will radically alter the experience of another person.” Prompts to good behavior were everywhere.

Another principle, "radical inclusion," is the antidote to the emotional abuse and social exclusions suffered in childhood. The consistent expectation of kindness is refreshing and softening, and people are just more present. I felt my own guardedness melt just a bit, with hugs, gifts, conversations, and gentle heckles.

Developmental psychologists find that play is the cauldron of intellectual, creative, and social development in childhood, and according to the Burner census, many people come to the playa just for that. The playful mood is their "top priority."

Everything that can be climbed on, is:

(Photos by Arjun Divecha)

You can be a flamethrower, safely:

Serpent Mother (photo by Jordana Joseph); Fire safety rules (photo by Arjun Divecha)

Puns are everywhere:

Burning Man: What Where When (photo by Arjun Divecha); Camp Nevada (photo by Diana Divecha)

And a Disney singalong and Thriller flashmob are open to all comers—not something we normally have an opportunity to attend.

The Bunny March Against Humanity herds humans into a bus and they exit dressed as bunnies. Humans haven’t done such a good job of being in charge, the organizers say. So let’s give the bunnies a chance.

“The only cure for reality,” says the author Gary Lindberg, “is imagination.”

And finally, our sense of wonder was on full throttle much of the time. The location itself is dramatic, and the playa was saturated with one stunning installation after another.

(Photos by Diana, Arjun, and Zai Divecha, and Julie Light)

The burning of The Man at the end of the week might not just represent an anger toward the political and economic establishment but perhaps a rebellion against the colonization of the heart and spirit as well.

This is a struggle we are all wired for. As we watched a group of young yogis strain, falter, and ultimately succeed in positioning themselves atop giant letters, an observer called out encouragement, shouting “This is what it is to LIVE!”

DREAM LIVE BE OK (photo by Arjun Divecha)