photo credit AlonzoDesign

Thirty years ago, when my Indian mother-in-law first learned that I was pregnant, she had some advice: Eat a lot of ghee (clarified butter), think pleasant thoughts, and gaze upon beauty.

Charming, I thought. I had a full time job with a two-hour commute. Where was there any time for meditative reflection? Still, she planted a thought in my mind, and I began to wonder. Was there a connection between my internal state and the development of the baby growing within me?

Folk wisdom and cultural beliefs throughout history have maintained that a woman’s emotions affect the fetus. Animal studies have shown that maternal stress, especially, can affect offspring—but it’s not been clear exactly how relevant those findings are for humans. In the last 15 years, though, research on human mothers and babies has caught up to show that my mother-in-law was at least partly correct: A pregnant woman’s emotional state—especially her stress, anxiety, and depression—can change her child’s development with long-lasting consequences.

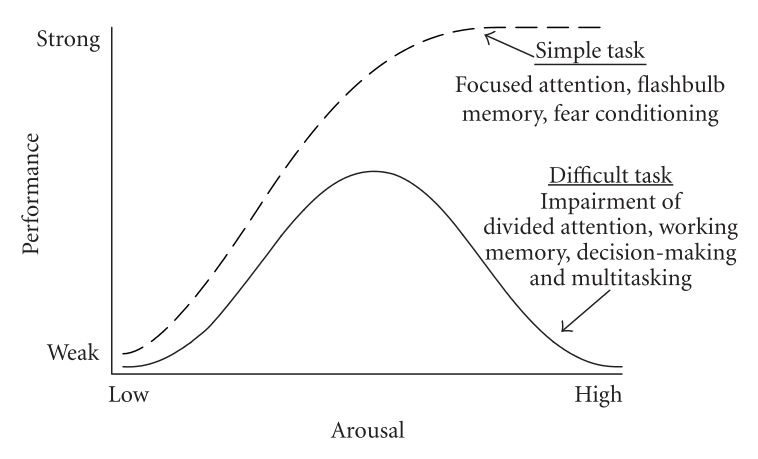

Yerkes and Dodson, 1908, in Diamond, DM et al. (2007).

Some stress is good.

When it comes to stress, psychologists often affirm the Goldilocks approach: too little is not good, as it makes us passive. And too much is not good because it can overwhelm us and contribute to emotional upheaval and physical disease. Along the spectrum, there’s a “just-right” amount of stress that helps us to function optimally in most situations.

The Goldilocks principle (called the Yerkes-Dodson law, in psychology) seems to be true in pregnancy, too. “The human brain requires sufficient, but not overwhelming, stress to promote optimal neural development both before and after birth,” writes researcher Janet DiPietro of Johns Hopkins University.

Pietro and colleagues studied pregnant women who were mentally healthy, well-educated, and had low-risk pregnancies. Midway through the pregnancies, Pietro measured the level of the mothers’ psychological distress (stress, anxiety, or depression). After the babies were born, she tested their development at six weeks and then again at the two-year point. She found that babies whose mothers had mild-to-moderate distress were more advanced in their physical and mental development. Another study showed that the babies’ brain development benefitted from a little prenatal stress, maturing a bit faster, with quicker connectivity among neurons.

Does that mean that women should welcome stress in order to boost their fetus’ development?

Absolutely not. According to DiPietro, the normal stresses of modern life are enough already. “The last thing a new mom needs is to head into newborn baby care stressed and exhausted.” In other words, healthy women leading reasonably normal lives can “stop worrying about worrying.”

But too much stress can be harmful.

On the other hand, when women experience severe stress during pregnancy, their babies can be at risk for serious problems. What kinds of stresses are harmful?

In studies on pregnant women, intense stress has been defined to include the following: the loss of a loved one; war; a major catastrophe like an earthquake, flood, fire, or terrorist attack; and interpersonal violence. These stresses have been linked to subsequent miscarriage, prematurity, or low birth weight in infants.[1] Stress that is chronic—like poverty, homelessness, racism, and discrimination—can also lead to low birth weight, as well as later physical and psychological problems. Babies whose mothers experienced these kinds of toxic levels of stress while pregnant are statistically more likely to have respiratory and digestive problems, irritability, or sleep problems in the first three years of life. They are also more apt to experience developmental problems, with cognitive, behavioral, social-emotional, and health issues that suggest neurodevelopmental changes that ripple into adolescence and adulthood. Many of the studies were careful to rule out other potentially confounding environmental factors in order to isolate the effects to the prenatal environment.

photo credit Ijubaphoto

photo credit monkey business images

A woman who experiences depression is also cause for concern. Newborns of mothers who were depressed during pregnancy are four times more likely to have a low birth weight than babies born to mothers who are not depressed. When women are depressed during pregnancy, there’s also a greater likelihood that they’ll suffer postpartum depression, which can become a major challenge for the whole family. Not only does the mother suffer, but research shows that depression in the primary caregiver is one of the strongest predictors of poor developmental outcomes in children. These children simply do not receive the normal interpersonal attunement and feedback they need in order to grow in emotionally healthy ways.

Even anxiety about being pregnant can be cause for concern. Research shows that “pregnancy-related fears”—worrying about an unplanned pregnancy, a specific medical risk, the fetus’ health, labor and delivery, or your ability to be a good parent—can be problematic in high doses. Excessive levels of anxiety (as opposed to what you worry about) are correlated with a greater likelihood of having a preterm birth. Also, pregnant women’s high levels of anxiety are correlated with later problems in children, including a difficult temperament, behavioral and emotional problems, anxiety, problems with attention regulation, impulsivity and hyperactivity, immune functioning and autoimmune disease, cognitive problems, and stress regulation.

Fetal stress and infant temperament

Psychologists have long known that babies enter the world with different temperaments. Some babies seem easy and sociable; others are more reactive, difficult to soothe, and are more sensitive to their environment. Until recently, scientists thought babies were “just born that way,” with temperaments that were “constitutional,” part of their makeup, or “inherited” from parents.

But the new research on fetal development changes that notion, and our understanding has progressed toward an interplay between biology and environmental influences—even before birth.

Catherine Monk, Professor of Medical Psychology in Psychiatry and Obstetrics and Gynecology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and her colleagues study the long reach of prenatal influences, especially among women who suffer from depression, stress, and anxiety. They found that some fetuses register mothers’ stress, and that fetal reactivity correlates with infant temperament at four months.

Monk and her colleagues brought 50 pregnant women into the lab and monitored the fetal heart rate while the women completed the Stroop Test, a mildly stressful mental task. Fetuses of women who were clinically depressed or anxious showed they registered the performance stress of their mothers, by the changes in their heart rates during the task. Later, when the babies were four months old, researchers assessed their temperaments by watching how reactive they were to a range of new stimuli (sounds, sights, smells), and some important patterns emerged. In particular, fetuses who had greater heart rate changes during their mothers’ task were more likely to be highly reactive at four months of age.

Subsequent studies have shown while the heart’s reaction to stress is important, the recovery from the stressor—how soon the heart returns to baseline—is also predictive. A quicker heart-rate recovery in the fetal period predicts an easier temperament and even more prosocial behavior later in childhood.

The fetus’ response to stress and the ability to return to baseline, may be the earliest sign of a fetus’ emerging stress regulation system, which in turn is the foundation of temperament (reactivity and regulation). The stress regulation system involves complex processes throughout the brain and body, and its effects cascade through complicated pathways into all the other areas of development. In infancy, the stress regulation system affects babies’ ability to form an attachment with others, to explore and learn about their world, and to receive feedback from others that helps them grow. It also affects their health and immune systems. Even for adults, scientists find that over the entire lifespan, the ability to manage the ups and downs of our interior worlds—stress, emotions, energetic “arousal,” and positivity—affects our physical and mental health, relationship quality, decision-making, and even creativity. Some studies assert that stress regulation has consequences for education, employment, and overall life satisfaction.

But a baby isn’t born with a thermostat set to some ideal of normal. In utero, the fetus is programmed to listen for cues about their future environment and start adapting accordingly.

“Theoretically, it’s an elegant evolutionary adaptation,” Monk told me in a recent interview. “The pregnant female communicates to her offspring cues about what the postnatal world is like, and the adaptation starts in utero.” But problems arise when the fit between the stone-age brain and the modern world is misaligned. “It could be advantageous to be reactive and vigilant if you’re in a dangerous postnatal environment,” Monk explains. “But we’re not facing bears in the woods now, so maybe the system for prenatal adaptations made to anticipate adverse environments (the environments that are eliciting stress and anxiety in pregnant women) aren’t adaptive for our modern world.”

The stress regulation system operates much like a thermostat that sets the room temperature, increasing the heat or turning it down to achieve a desired range. When we perceive a threat, the sympathetic nervous system activates a fight-flight-or-freeze response throughout the body and brain. When we judge that the threat has subsided, the parasympathetic system turns on to try to bring the whole system back to a resting state.

Because the biological “hardware” is just forming during the fetal period and early infancy, these are crucial times for setting the stress baseline in each fetus and young baby.

How do mother’s feelings get through to the fetus?

Scientists are curious about how stress reaches a developing fetus. This research is just in its early stages, and much more needs to be learned. But so far, scientists are focusing on a few mechanisms which may operate together or independently:

One is cortisol, a stress hormone that’s a downstream product of the body’s stress response. Women with anxiety and depression have higher levels of cortisol. And there is some evidence that when the placenta registers higher levels of cortisol from the mother, it creates an epigenetic change—a molecular modification to the gene that changes how it functions—that allows more cortisol through to the growing fetus, which in turn affects the stress regulation system.

“The placenta is highly susceptible to maternal distress and a target of epigenetic dysregulation,” Monk and colleagues write.

Inflammation is another focus of investigation. The pro-inflammatory cytokines—proteins that impact the behavior of cells and resulting immunity—may play a role, but the research on the exact pathways involved is still in the early stages.

Scientists are also looking at the role of infection and the microbiome, but there is no conclusive evidence at this time.

There are other complications, too. For example, one gestational period doesn’t seem more sensitive than another, but the impact of stress might vary depending on which areas of the brain are developing when the stress occurs. And while both sexes are affected, there are hints that male and female fetuses might react differently. For example, some research shows that female fetuses are more reactive to stress in utero, but other studies suggest males and females react similarly, but that males recover more quickly.

How much control do pregnant women have?

It should be obvious that almost every source of major stress—war, the loss of a loved one, violence, poverty, homelessness, a demanding workload, etc.—is outside the control of the woman experiencing it. But given that we live in a culture that frequently blames mothers for whatever happens to their children, I was concerned that this new research might be wielded against women.

“Could this research be used as a new form of mother-blaming?” I asked Monk.

“I think about this a lot,” she replied. “I don’t want my research to be adding stress to a woman’s life.”

Monk pointed out several caveats to the findings:

First, she cautioned that the research is just beginning, and we have to consider that these are correlations, not cause-and-effect. The associations have been shown repeatedly by different researchers, but it is not possible to complete a scientifically controlled study of intense stress on humans that would sort that out.

Second, Monk explained that a pregnant woman’s stress is just one of many “exposures.” There are numerous biological and environmental influences on development: The air a woman breathes, the water she drinks, the nutrition she ingests, and whether she exercises, gets sick, or is exposed to toxins. There are genetics. The father’s sperm quality matters, too, and is affected by his age, health and risk factors, and even frequency of physical exercise. Support from partners, families, and friends is important in mitigating stress.

Third, we should care for pregnant women more preventatively. “If we want to have a healthy population, a healthy workforce, then society is responsible,” Monk says. “So let’s take care of women and families early on with policies and programs that support them.”

Fourth, some stress is modifiable. “I see homeless women living in shelters, and I see busy medical doctors juggling family life with their practices,” says Monk. “One person can’t move the level of poverty in the country, but we can do something to help people cope with it. We really do know how to de-stress people and help them with depression and anxiety.”

And finally, stress hardware isn’t completely formed by birth. Once born, the quality of early caregiving continues to alter the epigenome that regulates stress, emotions, and behavior, dialing up or down the expression of genes that set the baseline for stress regulation. In many cases, good caregiving after birth can offset a rocky prenatal start.

How much stress is too much?

“How can women know if their stress levels are harmful or normal?” I asked Monk. “Are some kinds of stress worse than others?”

She replied, “Science is not at a place yet of saying that one kind of stress is worse than another. In our clinic, we see women in extreme stress, and what matters is how much, and what inner and outer resources they can bring to the experience.”

Monk listed some indicators of harmful stress:

When stressful feelings are chronic (symptoms might include an inability to get up in the morning, a continual low mood, not eating or sleeping)

When there’s prior exposure to trauma or abuse (which the anticipation of parenting might reactivate)

When a person’s life foundation is weakened by repetitive daily stresses (e.g., “Will I lose my job?” “Where’s my next meal coming from?” “Are we getting a divorce?”)

Or continual feelings of being overwhelmed

In addition, Monk and her colleagues use the Perceived Stress Scale to measure stress in their research subjects. They found that women in poorer mental health (comprising about 20% of their samples) score around a 26 or less on the scale. Items such as “I feel like I don’t have control,” “I often feel overwhelmed,” and “I feel like I can’t get things done,” are indicative.

Monk adds, though, that fewer psychologists are trying to measure a person’s amount of stress, and instead are looking at how they function across different areas of their lives. For example, a person might ask, “How am I functioning now compared to six months ago?” Or, “How am I functioning cognitively, physically, interpersonally, or emotionally?” This approach offers more useful information, Monk notes, allowing the person to leverage what is going well and to shore up what is not.

What helps?

Every person has unique vulnerabilities and strengths, and every situation is different. But research confirms that although we might not be able to control what happens to us, we have some control over how we react. And that matters. We can change our responses to stress through self-care (nutrition, sleep, and moderate physical activity); increasing our repertoire of emotion strategies for coping; having positive experiences; and seeking support from others. A strong support network of engaged partners, helpful family members, and good friends can buffer the ill effects of stress. Techniques like meditation and mindfulness have been shown to reduce stress and create better pregnancy outcomes and physical health.

As an example, Monk and her colleague Elizabeth Werner developed a four-session intervention that reduces the risk of depression in pregnant women by half. The PREPP program (Practical Resources for Effective Postpartum Parenting) reaches out to women through OB-GYN offices, and offers them education on three topics:

Parenting skills (e.g., How to help babies sort out day-night cues; encouragement for carrying the baby when he’s not crying, etc.)

Psychoeducation (e.g., What to expect about babies’ crying); and

Mindfulness and self-reflection (e.g., Examining how you were parented)

This intervention reduced depression and anxiety in mothers, and their babies became better self-regulated as well.

“By learning more about handling their baby, a mother may literally be facilitating their baby’s regulation along with their own. Mothers and babies get onto a bidirectional, more positive cycle,” Monk says.

As for me, since this knowledge wasn’t around to confirm my mother-in-law’s advice during my pregnancies, I hedged my bets. I knew I carried high levels of stress from a turbulent childhood, so I took some extra care. I exercised, was thoughtful about my food, and took a prenatal yoga and meditation course. But by the second pregnancy, I was frequently overwhelmed with panic attacks at the prospect of managing work and two children. Already my energy was low, and I filled in with chocolate milkshakes when I should have rested. Fortunately, both daughters did fine in the long run and are well-adjusted adults. But many women face graver challenges, and as a society, it’s our responsibility to protect and support them. Many countries have made children a collective investment, but in America, tragically, we haven’t. It’s a big problem—and a big topic, which I’ll save for a future blog entry.

photo credit RusianDashinsky

More Resources

How pregnant women’s emotions affect prenatal and child development:

Origins: How the Nine Months Before Birth Shape the Rest of Our Lives, by Annie Murphy Paul.

Catherine Monk’s videos on prenatal stress here.

Stress reduction in pregnancy:

Newman, K. M. (2016, August 17). “Four Reasons to Practice Mindfulness During Pregnancy,” Greater Good Magazine. Retrieved from https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/four_reasons_to_practice_mindfulness_during_pregnancy.

Bardacke, N. (2012). Mindful Birthing: Training the Mind, Body, and Heart for Childbirth and Beyond. New York, NY: HarperOne.

Mindful Birthing Network: Mindful birthing. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.mindfulbirthing.org/.

Hardwiring happiness: Zimmer, E. (2015, June 24). 082: Dr. Rick Hanson. The one you feed. Retrieved from http://www.oneyoufeed.net/rick-hanson/.

Introduction to mindfulness-based stress reduction:

Palouse Mindfulness. (2015, August 28). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (UMass Medical School, Center for Mindfulness). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TA7P-iCCcY.

Sega, A. (2016, August 22). Jon Kabat Zinn: Practical Stress Reduction. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fjNPbErciU.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2016). Mindfulness for Beginners: Reclaiming the Present Moment and Your Life. Boulder, CO: Sound True.

This is one of my favorite resources for self-development:

Hanson, R. (n.d.). Rick Hanson. Retrieved from http://www.rickhanson.net/rick-hanson/

How to find out about, and advocate for paid leave from work:

Find out if your state has paid family and medical leave protection here:

National Partnership for Women and Families. (n.d.). Paid leave means a stronger nation. Retrieved from http://www.nationalpartnership.org/issues/work-family/paid-leave-means-map.html.

Quick economic statistics re: the costs to both employers and employees of NOT having paid leave: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1geQNdDBd2MDBvzvOMJg_YKdfVqSsduWZ/view.

Companies that offer paid leave, and their rationales for doing it:

National Partnership for Women and Families (2018, January). Companies with new or expanded paid leave policies (2015-2018). Retrieved from http://www.nationalpartnership.org/research-library/work-family/paid-leave/new-and-expanded-employer-paid-family-leave-policies.pdf

An article on how businesses can adopt paid leave:

Williams, J. C., & Massinger, K. (2015, November 23). “Need a Good Parental Leave Policy? Here It Is.” Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/11/need-a-good-parental-leave-policy-here-it-is.

How to negotiate a leave, from the Harvard Business Review:

Gallo, A. (2012, October 25). “How to Negotiate Your Parental Leave,” Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2012/10/how-to-negotiate-your-parental-leave.html.

The effects of paid leave on child health and employee retention:

National Partnership for Women and Families. (n.d.). Studies on the Effects of Paid Leave. Retrieved from http://go.nationalpartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=issues_work_library_paidleave_research#effect

Reference

Yerkes and Dodson, 1908, in Diamond, D.M., Campbell, A.M., Park, C.R., Halonen, J., & Zoladz, P.R. (2007). The temporal dynamics model of emotional memory processing: A synthesis on the Neurobiological basis of stress-induced amnesia, flashbulb and traumatic memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson law. Neural Plasticity, article ID 60803, 33pgs. doi:10.1155/2007/60803

Footnote

[1] Low birth weight, sometimes referred to as “small for gestational age,” occurs when the weight at birth is lower than expected for the length of the pregnancy. It is a risk factor for subsequent development. The U.S. has the one of the highest rates of babies born with low birth weight—about 1 in 13. Babies who are born very small for their gestational age are more likely to go on to develop problems, but most low-birth-weight babies who receive good nutrition and sensitive, affectionate care and stimulation, catch up and do just fine.

Additional Photo Credits

Top panel, left to right: MaxRiesgo, RapidEye, vm, DragonImages

Middle panel, left to right: FatCamera, photominus, Dean Mitchell, martinedoucet