When I told people I was going to my 40th high school reunion, I might as well have said I was jumping off a cliff. Almost across the board, the reaction was shock, though the reasons varied. Granted, I hadn’t been in touch with my classmates, so some degree of surprise was legitimate. But my friends and family also projected their own reasons: high school had been the “worst time of their lives”; that they had never “fit in”; they didn’t want to open their present lives to judgment. But I’m a developmental psychologist, and I wanted to understand what a reunion ritual might mean. Nothing is more interesting to me than discovering how children grow up and their lives turn out.

As the date approached, I finally became apprehensive myself. Most of us had been together since kindergarten, but what if I didn’t recognize people after forty years? After all, I now have silver hair and 40 additional pounds; others would also have changed. Or what if we didn’t have anything to talk about? How would I react to an old “flame,” or he to me? Could I finally uncover the story behind a friend who had so traumatically “dropped” me in sixth grade? When nervous jokes started showing up on the Facebook reunion page, I saw that I wasn’t the only one with anxiety. I recruited a childhood friend to go with me.

“I’m only doing this for you, you know,” Vic joked when she greeted me at my hotel. Our mothers went to high school together and been friends long before we were born. Vic remembers the fuzzy socks I wore in second grade and how my father had carried me into school in his arms when my broken leg was in a cast. I remember making vinegar and baking soda volcanoes at Vic’s house and singing soprano next to her in choir.

We arrived at the Curling Club (home to the winter sport of sliding granite stones on ice) to a frenzy of slightly boozed-up greetings. About a third of my class of 140 was there. A current of excitement crackled through the crowd—hails from across the lawn; flying wisecracks and boisterous teasing; and enthusiastic, if somewhat self-conscious, hugging. It was a relief to find my old friend Dave, who was just as unruffled as I’d remembered him—a straight shooter, unperturbed by his surroundings. He had worked for a time for my father, a milkman; his mother had been my beloved third grade teacher. I was happy to meet Dave’s wife, and a meaningful conversation ensued about parents, illness, children, and more.

Sociologist Vered Vinitzky-Seroussi has observed that high school reunions can trigger a sudden threat to one’s identity. In the space of a short gathering, we are called upon to reconcile past expectations with our present reality, among people who shared that past. At my reunion, the actual list of predictions that our peers had made about each other 40 years ago hid amidst the memorabilia. “Diana will run a computer dating service,” it read, and the old memory of craving connection amidst my chaotic environment flashed. Other predictions were equally unpredictive: that a high school romance would end in marriage (it didn’t) or that a career would peak in a grocery store stockroom (it didn’t); and predictions for women centered on marriage and children. Predictions can be entertaining, but since these weren’t about activating our best future selves, I regretted their presence. Reunions are not just happy gatherings, Vinitzky-Seroussi writes. They “telescope the life course” and create pressure to evaluate, or protect, or project our choices, often in the space of a very short, catch-up conversation.

But this was not our tenth or even twenty-fifth reunion, the early ones that Vinitzky-Seroussi studied. This was our fortieth, a time when life achievements are behind for most of us and some are even looking toward retirement. Fortunately, I felt well-anchored in the present, and I think others did, too.

The conventional wisdom about reunions is that people can surprise you, and I found that to be true. Who would have known that the quiet boy in the back of the band would be a pillar of the community as the trusted funeral director? Or that the guy who seemed lost in high school would be so crisp and successful at 58? Psychologists use the terms “equifinality” and “multifinality” to describe how very different paths can lead to similar outcomes, or, conversely, how similar paths can lead to very different outcomes. At the same time, our perceptions of what’s important changes, too: The kids who once dominated in popularity might now appear boring and superficial, and the former “outsiders” often turn out to be the really interesting ones. And yet when I asked Vic if she recognized everyone, she replied, “Not so much from their faces, but their energy—it’s the same.”

Even though we all shared a large part of our pasts, we couldn’t have truly known each others’ lives while we were children. A few kids had seemed to sail through with equanimity—they ran the student council at school and collected maple syrup at home–but even then, there were hints of malaise. I knew that it wasn’t right that the gentle, deer-like boy who sat in front of me in seventh grade homeroom smelled like alcohol and cigarettes. Another child was rumored to have been abused, though there was no action taken to protect her. I was a high achiever but suffered with parents who were in constant conflict; they struggled with mental health and substance use issues. Many parents were alcoholics before the disease was even named.

Psychologists now know that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are predictive of later physical and mental health problems, including heart disease, depression, and suicidality. Research suggests that about a third of kids are lucky enough to escape trauma, but about a quarter suffer such high doses that it affects brain development, immune and endocrine functioning, and can create mental and physical disease systems that reduce the lifespan by an average of 20 years. How different might many students’ lives have been if an adult had recognized their feelings and had the skill to approach them and say, “You look down. What’s going on, and can I help?” Today, innovative schools throughout the country are feathering emotional skill development into their academic curricula, and studies show that both individual kids, and the school as a whole do better. Pediatricians, too, are beginning to screen for ACEs and offer early intervention services to families and children at risk.

Childhood is not easy, even at the best of times, and middle school is an especially stressful period. Conventional wisdom used to hold that it was the changing sex hormones that made kids “crazy,” but scientists now understand that puberty kicks off changes in the brain that make youth more emotionally sensitive, more sensitive to their social world, more willing to take risks, and more vulnerable to mental illness and addictions. Combine all of that with changes in schools, new peer groups, or family troubles, and you quickly get a pile-up of stressors that can be overwhelming.

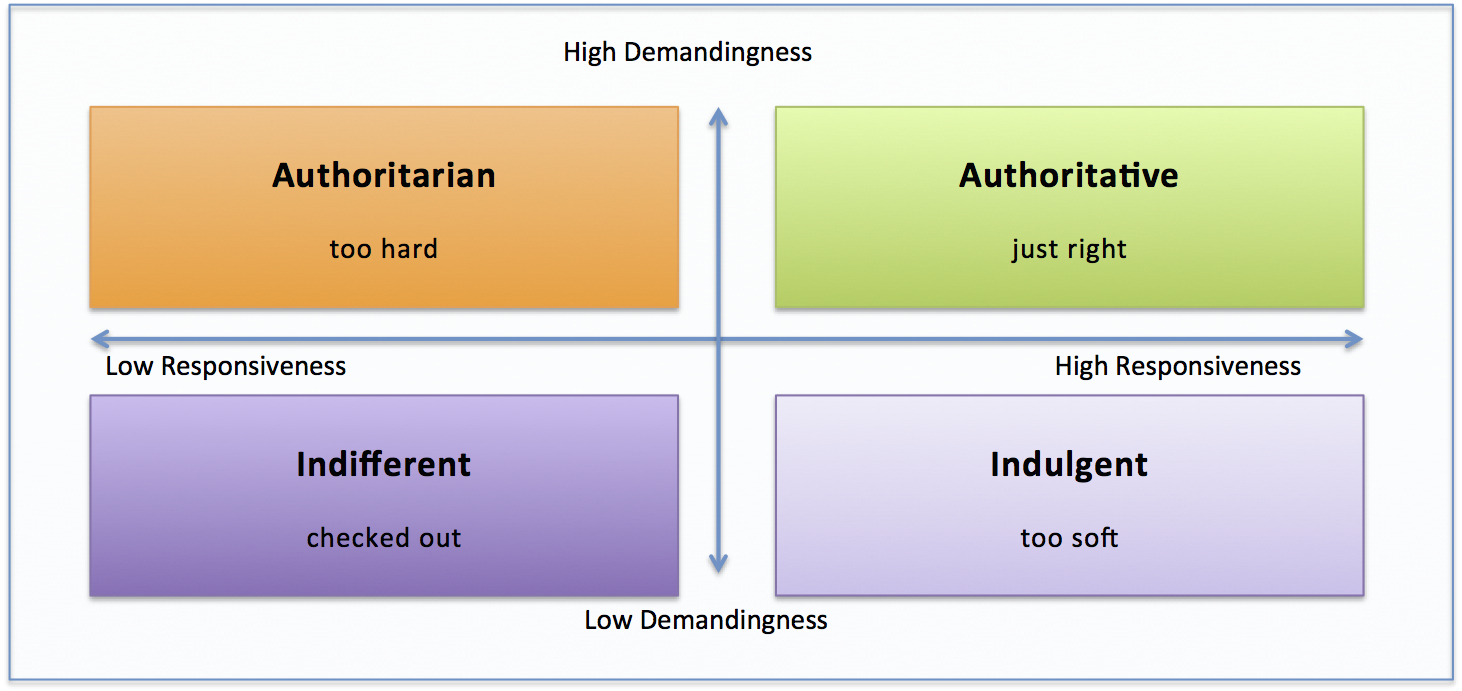

Jockeying for status in peer groups begins as early as the fifth grade, and, in my day, peer dynamics were raw and lacking any guidance. Consistent with the research, it was the male athletes and the conventionally pretty girls (especially cheerleaders) who were conferred high status, and kids who were “different” were often marginalized—through teasing, exclusion, and gossip. Girls who physically matured earlier than average, or boys who matured later than average, were at greater risk, just as they are today. Too tall, too skinny, too heavy, too awkward, too shy, too country, too slow…the “faults” can be endless.

Kids naturally form and re-form friendships, but without real social skills, the process can be excruciating. In sixth grade, I was shattered when my best friend of six years decided one day to simply stop talking to me. While it’s natural for a child to feel ready to find new friends, this particular friend had had no skills with which to explain her needs. Her silent treatment left a mark, and I used it both as a cautionary tale for my own children and an illustration in the college courses I taught on teen development. Research now shows that humans are such intensely social creatures that social ostracism lights up physical pain pathways in the brain; it can be more damaging than even physical abuse. Sometimes, I imagine how our friendship “breakup” could have gone differently, had we had the social skills kids can learn in school nowadays to navigate peer conflict. Though my well-being is no longer affected by that experience, I was curious to know my former friend’s side of the story. Yet when we greeted each other at the reunion, we didn’t get much beyond a hello. I took that to mean that it was not likely to be the place—or perhaps the person—where such a conversation could happen.

“Humans are storytelling, story-loving creatures,” says psychologist Matthew Lieberman, author of Social Brain, Social Mind. One of the most powerful ways we understand the experience of being human is by constructing a narrative of our lives. Young children begin this process as soon as they learn the word “I,” and parents begin telling them stories about when they were little. And at the other end of lifespan, elders engage in a “life review,” telling and retelling their stories to help them make sense of their lives.

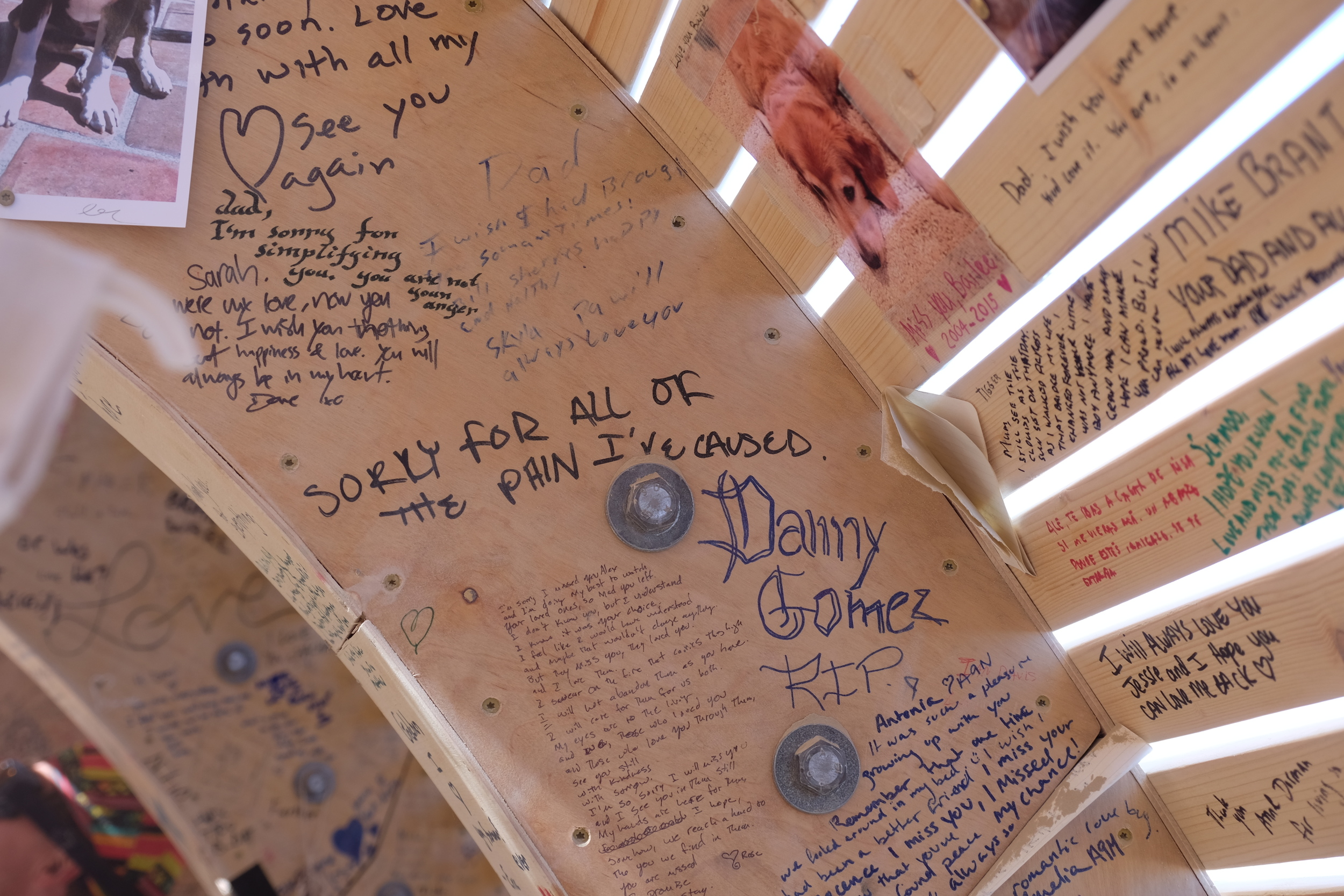

Reunions—where our past selves meet our present selves—can be a special opportunity to re-weave our stories. I observed it happening all evening. One woman who had seemed defiant and tough in junior high apologized to the PE teacher, telling her that she hadn’t meant to be the teacher’s “nemesis” but in fact was a military kid who got moved around a lot.

“I never knew that,” the teacher breathed, empathically.

A man who had been a geek before geeks were cool enthusiastically shared that he was an inventor, held patents, had designed a part of the space shuttle and a medical device, and had made millions doing so.

A friend divulged her confusion about some same-sex experimentation that had gone on at a childhood sleepover. Of course there had been no framework for normalizing that, or even language to name it.

I, too, had a story to revise. When a popular biology teacher’s name came up, I shared that six years after we’d graduated, he had prevented my Lutheran church from marrying me and my husband, because my husband is from India. “He’s not a good guy,” I grumbled about the teacher.

The life stories flowed, from what it’s like for a Minnesotan to be transplanted to the Deep South, to taking care of grandchildren, to being the youngest in a senior citizen woodworking shop, to losing a child. There was a lot of loss and growth to process, as well as joy to celebrate.

One evening is not enough time together to truly span 40 years; it’s just a sliver of reality. But I happily put new numbers and email addresses into my phone. I want to keep up with some old friends, and I discovered new ones that I’d missed earlier.

And that old flame?

“I learned from you,” he told me. “Your family had high expectations, and I craved some of that.”

“You sheltered me at a stormy time,” I replied, remembering his laughter and easy-going manner.

Class reunion? For me, at least, it wasn’t so scary. What we went through together mattered, and bearing witness to one another’s stories—from our shared past and the years that had followed— felt like a good way to honor that.