photo by Sahil Merchant

"Tell me about the joys of being a new parent," I prompted my niece, whose little baby is five months old. She is 34, works full-time, and is married to my nephew.

The transition to parenthood is profound, as many parents already know. Developmental scientists consider it to be one of the most massive reorganizations in the lifespan, changing the brains, endocrine systems, behaviors, identities, relationships, and more, of everyone involved.

Kelly's answers had a quiet and whimsical grace.

"There is nothing more beautiful in this world than his smile," she said. "Or watching him discover something new. Last night he found the upper register of his voice, so he spent five minutes shrieking at a high pitch, playing around with the newfound note."

Kelly is a beautiful person, so I wasn't surprised to hear her speak appreciatively about her young son. And, in recent and evolving research, scientists are charting a "global parental caregiving network" that gets shaped in a new parent's brain to bring about some of the very thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that Kelly and other new parents experience.

In 2014, Ruth Feldman, a researcher in Israel and at the Yale School of Medicine, conducted an experiment with her colleagues. They went into the homes of 89 new parents, collected samples of oxytocin (the bonding hormone), and videotaped the parents interacting with their newborns. Later, the researchers put the parents in a functional-MRI machine and replayed their videos back to them, observing which parts of parents' brains "lit up" when they saw their own infants (versus videos of unrelated babies) .

The researchers found two main regions of the brain particularly active in new parents. The first is the "emotion-processing network." This is located centrally and developed earlier in evolution than the neocortex (see below). It involves the limbic, or feeling, circuitry and includes:

The amygdala, which makes us vigilant and highly focused on survival

The oxytocin-producing hypothalamus, which bonds us to our newborns

The dopamine system, which rewards us with a squirt of the feel-good hormone to make us motivated and enjoy parenting

All together, this network creates a heightened emotionality in parents in response to their babies. In fact, according to researchers Laura Glynn and Curt Sandman, the volume of gray matter (or number of neural cell bodies) increases in the above regions in new mothers and is associated with their positive feelings toward their infants. (See Glynn and Sandman's review article on brain changes in pregnant mothers.)

The second region is the "mentalizing network" that involves the higher cortex, or the more thinking regions of the brain. This area, along with additional superhighways that develop between the emotion and mentalizing systems, focuses attention and grounds in the present moment: Who couldn't stare at a new baby forever? It also facilitates the ability to "feel into" what a baby needs: Areas of the brain that involve cognitive empathy and the internal imaging of, or resonance with, a baby, light up. These regions help a parent read nonverbal signals, infer what a baby might be feeling and what he/she might need, and even plan for what might be needed later in the future (long-term goals). These regions are also associated with multitasking and better emotion regulation. In other words, parents' brains are remodeled to protect, attune with, and plan for their infants.

Other research has found that hormonal changes in pregnant women dampen their physical and psychological stress response, as if to make more space to tune in to their babies' needs.

But along with all these changes, there seems to be a collateral cognitive hit: In a meta-analysis of 17 studies, 80% of women reported impaired aspects of memory (recall and executive function) that began in pregnancy and persisted into the postpartum period.

photo by Kelly Merchant

Mothers aren't the only ones whose brains are remodeled. The brains of fathers, too, light up in ways that nonparents' brains don't. Feldman and her colleagues found that while the emotion processing network is most active in the biological mothers she studied, it is the mentalizing networks that are more active in the brains of fathers who are co-parenting alongside moms. The more fathers engage in caregiving tasks, the more oxytocin they produce, and the stronger the activation in the mentalizing areas of the brain.

Interestingly, in gay dads who are primary caregivers (half of Feldman's subjects), both emotion and mentalizing systems were highly activated by engaging in parenting. (For more on how parenting changes fathers' brains, I recommend the fun read, Do Fathers Matter? What Science is Telling Us about the Parent We've Overlooked, by Paul Raeburn.)

In other words, parenting is a very plastic and flexible process. While pregnancy prepares a mother's brain for parenting, the act of caregiving can produce upticks in oxytocin (the bonding hormone) and create neurological changes that support parenting in many adults--dads, adoptive parents, and other alloparents (any caregiving adults).

photo by Kelly Merchant

Kelly's husband Sahil is open about the new feelings he's having as a dad. "Winnie [short for Winter] is a curious, cheerful little person, and watching him develop and experience the world for the first time brings me endless amusement and joy. With Winnie, I've found new depths of love--it feels like a very biologically driven emotion."

While he is drinking in the sweet elixir of his baby, Sahil is also running his feelings through the thought circuitries. "Besides being afraid of the regular things--injury, illness, and such--I am also sad that his innocence will inevitably be eroded over time, and that he will inevitably experience all the various pains involved in growing into an adult."

Kelly admires her husband's changes and says that one of her greatest joys is "watching my husband develop into an incredibly loving, nurturing, and giving father."

Parents, naturally, continue to develop as individuals, and the arrival of a baby stimulates self-reflection. Observing Winnie moved Kelly to reflect on what must also have been the miracle of her own beginnings. "I'm fascinated by the fact that I, too, floated in a sack of amniotic fluid; that I, too, saw my hand for the first time and probably stared at it for 30 minutes straight, waving it in the air. Or that I, too, might have been startled by my own sneeze, or gas, or yawn."

Sahil says, "Having a child has given my life more meaning. For example, rather than working to earn money just for myself, to purchase various objects and experiences, I now have a great reason to do so. I'm more careful now, too. I have a child who depends on me, so I feel like I need to take better care of myself, so that I can be my best possible self to take care of Winnie."

Challenges

The joys of parenting are often felt more deeply than almost any other feeling humans are capable of having. But the challenges are great, too. "Every mom I knew was surprised by the impact of becoming a parent and wished she knew more about coping with it," writes Jan Hanson in Mother Nurture: A Mother's Guide to Health in Body, Mind, and Intimate Relationships. Hanson is a nutritionist who co-authored the book with her husband, the neuropsychologist Rick Hanson, as well as OB/GYN Ricki Pollycove.

There are challenges to parents' physical health: recovery from pregnancy and delivery, the adjustment to breastfeeding, disturbed nutrition, fatigue, and insufficient sleep. As you would expect, Kelly reports that trying to stay rational, keep conflicts down, and drive safely are difficult on three hours' sleep and/or when she's been up, exhausted, since 4 A.M. She is experiencing what researchers know: That proper sleep is critical to health and well-being, including mood, decision-making, performance, and safety.

There are psychological adjustments to the new parenting role, too. Some parents need time to recover from a difficult or complicated birth process. For some, parenting demands can trigger strong unresolved feelings from childhood, especially if it was traumatic or troubled. Hormonal changes, along with sleeplessness and the constant demands of a new baby, can create surprising new feelings, too: anger, sadness, feeling trapped or isolated--even guilt, fear, and inadequacy. Some parents have to wrestle with having lost a previous child, or perhaps they are parenting a difficult or differently abled child. Kathleen Kendall-Tackett writes about these psychological challenges, and more, in The Hidden Feelings of Motherhood: Coping with Stress, Depression, and Burnout.

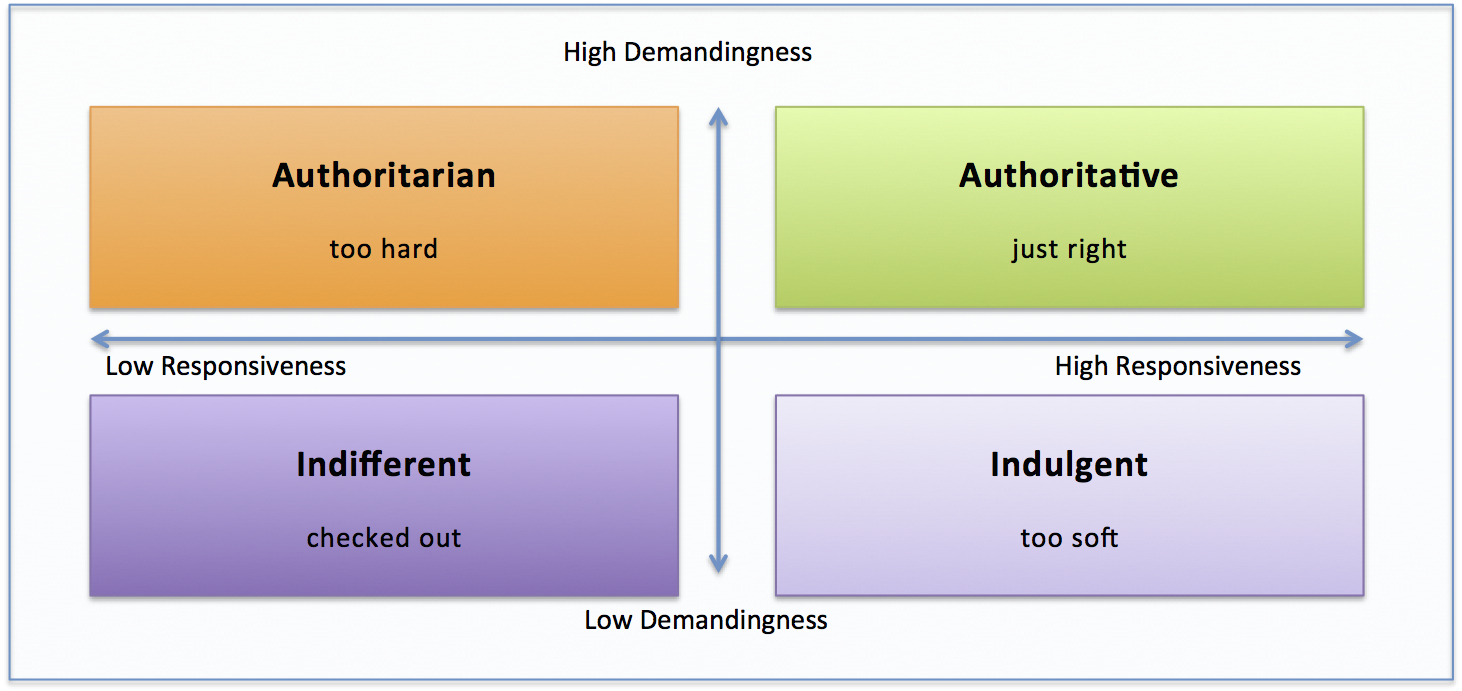

Having a new child introduces new challenges to the parents as a couple. Conflicts often increase in a relationship after the birth of a child, in part due to the "roommate hassles" of who will do what in the household as well as disagreements about parenting styles. Sometimes the sense of intimacy, closeness, and sexuality in a relationship can get derailed with the arrival of a little one. Couples are challenged to re-synchronize their relationship and develop a new sense of teamwork.

The couples who are most at risk for serious problems after the birth of a child, write parenting scholars Carolyn Pape Cowan and Philip Cowan in their book When Partners Become Parents, are those who were on the rocks before the child came along. Becoming a parent amplifies any pre-existing fissures in the relationship. Especially problematic are poor communication patterns--where one stonewalls, digs in, and/or refuses to budge, while the other escalates. In contrast, couples who have productive ways of working out new difficulties and challenges do the best adjusting.

After the arrival of a child, there are new logistics to deal with: new strains in managing a household, financial and legal concerns, when and how to go back to work, and figuring out childcare. Like many contemporary mothers, Kelly experiences the challenges as coming from both sides: the struggle to feel okay going back to work after three months versus the struggle to feel okay staying home without being criticized as a poor worker or an anti-feminist.

New parents also undergo a rearrangement of their social life, including how they interact with extended family and friends. Some friendship networks get reconfigured (not all childless people want to hang out with new parents). Kelly noticed that other people changed in their relationship to her as she became a parent. Many people offered unsolicited opinions, especially on the topics of sleep and clothing: "At times it felt that anyone who had once been a mother felt the need to say that my baby should put on more clothing. Even in 90-degree weather when he was sweating! And I was quite happy to be co-sleeping with Winter, but I was made to feel guilty about this on many occasions. Sleep is such a touchy topic, and many people tried to convince us to get Winter into a crib if we wanted what was best for him." Kelly found support from her sister who encouraged her to be firm about her internal compass in the face of many differing opinions: "Your only option is to learn to listen to yourself and know that you know your situation, and what works for your family, better than anyone else." Kelly adds that the most helpful exchanges are ones where she is encouraged to share how things are going, and in return hear a similar story and outcome. "Not only does it feel good to know I'm not alone in this, it educates me about what works much better than direct advice."

Rick and Jan Hanson and Ricki Polycove have seen so many thoroughly exhausted mothers in their practices that they identified a "depeleted mother syndrome," a condition where the mother's "outpouring, stresses, vulnerabilities, and low resources" are so overwhelming as to "drain and dysregulate her body."

The solution they recommend is threefold, focusing on lowering parenting demands, increasing supportive resources, and building resilience. Rick Hanson is a thorough, compassionate, skilled, and practical therapist, and Mother Nurture is therapy in a book: From one-minute soothers, to resolving childhood issues, there is much help in the way of cognitive, neurological, and commonsense approaches. Among other things, he provides suggestions for :

taking care of your body

small daily practices to improve outlook

reframing circumstances

concrete problem solving approaches

transforming painful emotions from the past

problem-solving sleep

vitamins to help with the nervous system

assessing neurotransmitters

staying connected to your partner with empathy

sharing the load

maintaining intimacy

healing hurt feelings

photo by Crystal Hanson

Kelly noticed that just as her identity started changing as a parent, there was a tendency for people to converse with her exclusively about motherhood. She was naturally thrilled that her loved ones were excited about Winnie, yet she longed for relationships that also nurtured her individual identity as a painter, a counselor, yoga enthusiast, and traveller.

As an American, Kelly is not alone in this experience. Kathleen Kendall-Tackett writes that in many non-industrialized countries, the postpartum period is a special time of "mothering the mother." New mothers are considered especially vulnerable so their activities are limited, they're relieved of normal work, and they stay relatively secluded with their babies while other relatives take care of them. Along with that extra care, there are special rituals and gifts that mark this as an important period. American mothers, in contrast, are quickly released from the hospital and are often even expected to entertain guests who come to visit the new baby. That difference in support, Kendall-Tackett says, is why in industrialized countries about 50-80% of new mothers experience the "baby blues," and another 15-25% have full-blown postpartum depression. In more traditional cultures where new mothers are exclusively nurtured, postpartum depression is "virtually non-existent."

Kelly agrees: "A mother needs to be nurtured and cared for because she is doing nothing for herself at this point. Everything is being given to the baby and I find little time to do things like even wash my hair or take a bath. Or connect with a friend. Even getting a hug from my husband can be hard in those times when a baby is especially demanding. When I do get that hug, I need it more than ever before."

The transition to parenthood is a huge transformation. And America, with no comprehensive child-family policy and no federal paid family leave policy--is a particularly unsupportive place to have a child. But the accumulating research is pointing to just how sensitive and important this period is for families. With a little knowledge and some foresight, parents-to-be, and their loved ones, can better plan for the transition. The rise in popularity of the postpartum doula (a person, usually a woman, who is trained to help new families in the home) is a step in the right direction.

Rick Hanson encourages new mothers--and fathers--to insist that others take their needs seriously. "Treat yourself like you matter," he says.

* * * * *

Further reading (some of these are oldies but still goodies):

On coping with the challenging feelings of becoming a new parent:

The Hidden Feelings of Motherhood: Coping with Stress, Depression, and Burnout (2001) by Kathleen Kendall-Tackett

*Mother Nurture: A Mother’s Guide to Health in Body, Mind, and Intimate Relationships (2002) by Rick Hanson, Jan Hanson, and Ricki Pollycove

When Partners Become Parents: The Big Life Change for Couples (1992) by Carolyn Pape Cowan and Philip Cowan

The Gentle Art of Newborn Family Care: A Guide for Postpartum Doulas and Caregivers (2012) by Salle Webber

On becoming a father:

Do Fathers Matter? What Science is Telling Us about the Parent We’ve Overlooked (2014) By Paul Raeburn

All In: How Our Work-First Culture Fails Dads, Families, and Businesses—and How We Can Fix It Together (2015) by Josh Levs

Home Game: An Accidental Guide to Fatherhood (2009) by Michael Lewis