Three months into the pandemic, I had the urge to see my 28-year-old daughter and her husband, 2000 miles away. She had weathered an acute health crisis, followed by community protests that propelled them both onto the streets to serve food and clean up neighborhoods. They were coping, but the accumulation of challenges made the mom in me to want to connect with and support them. So, together with my husband, my other daughter, and her husband, our family of six adults and two dogs formed a new pod inside my daughter’s home in the steamy heat of the Minneapolis summer.

As I packed, a wisp of doubt crept in. We six hadn’t lived together under the same roof, ever. Would I blow it? Would I “flap my lips,” as a friend calls it, and accidently say something hurtful? Some time back, in a careless moment of exhaustion, I had insulted my brand-new son-in-law with a thoughtless remark. He was rightfully hurt, and it took a long letter and a phone call to get us back on track.

My own siblings and I were raised inside the intractable rupture that was my parents’ marriage. Their lifelong conflict sowed discord and division in everyone around them. I worked hard to create a different, positive family climate with my husband and our children. My old ghosts were haunting me, though, and I didn’t want to ruin a good thing.

We change each other’s brains and bodies.

The field of developmental science has demonstrated that our connections with one another are paramount, even physically palpable. There is a great deal of research that tells us so.

For example:

Newborns appear helpless, but the abilities they arrive with are the ones that will draw them into human relationships: a preference for human sights and sounds over nonhuman ones; the recognition of their mother’s voice, language, and smell over the voices, languages, and smells of others; and more. In other words, infants are born biased to bond and attach.

Caregivers and babies even change each other’s bodies and brains. There are the obvious changes that pregnancy brings, of course. But the act of caring for a baby also changes both men’s and women’s brains, whether or not the caregivers are biologically related to the baby. Caring activates and grows the areas of the adult brain involved in vigilance, watchfulness, and safety; empathy and perspective taking; and feelings of reward and motivation—all qualities that help us want to care for and keep our babies safe. And dads’ testosterone levels even drop to help men be more sensitive to their babies.

Caregivers change their babies’ bodies, too. In the first few years of life, the quality of care we offer our babies turns on or off their genes that control the development of their stress-regulation system. This sets the child’s baseline for stress sensitivity and management.

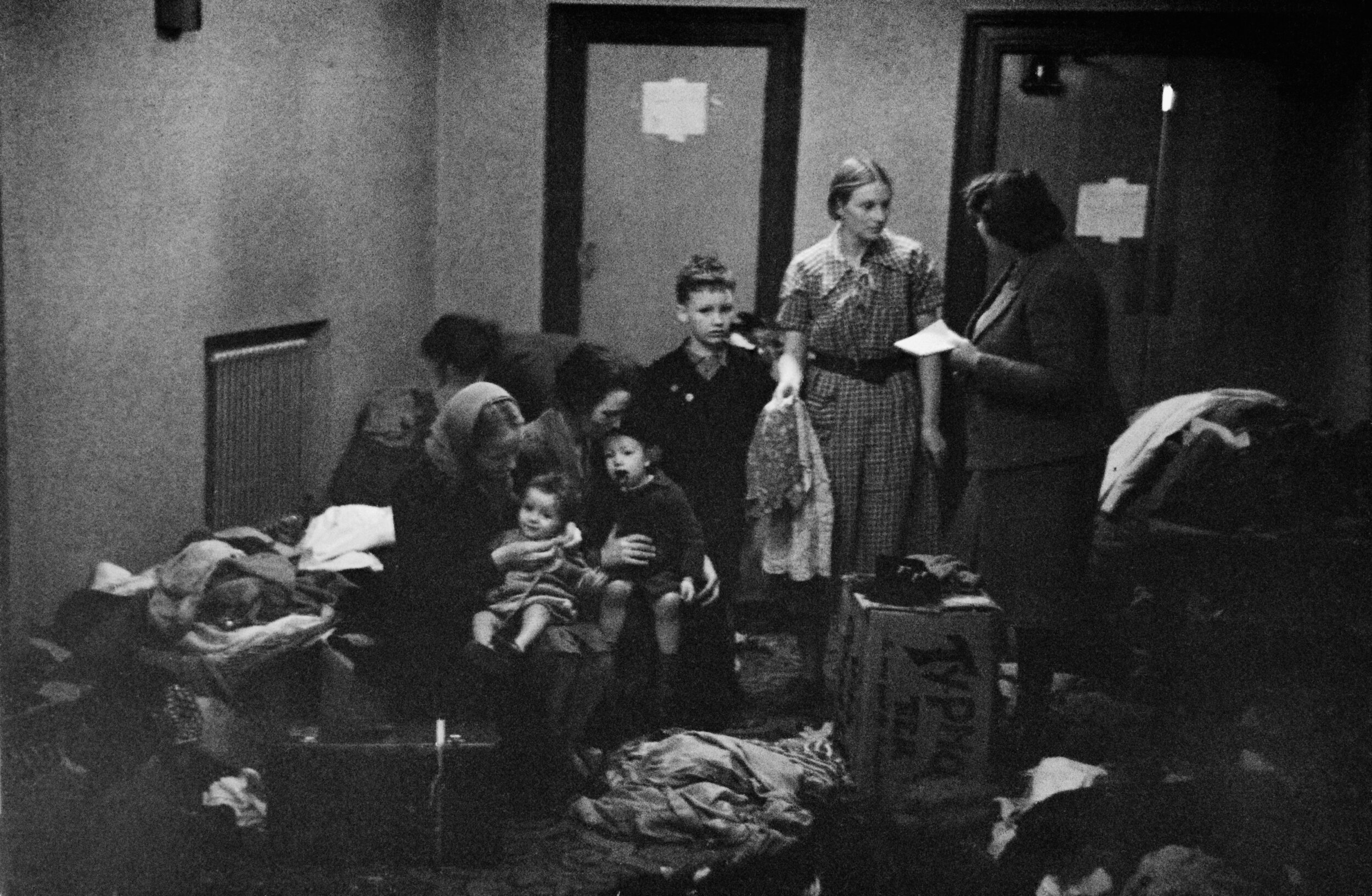

photo credit: Zan on Unsplash

We grow the biological foundation of babies’ positive psychology best when we’re within a window of synchrony, or harmony, with them. Ruth Feldman is a developmental neuroscientist at the Interdisciplinary Center at Herzliya (Israel) who has analyzed babies and parents while they interact. Earlier, she studied jazz, observing how musicians improvise together, playing off of one another in spontaneous but coordinated riffs. That appreciation set her on a career of studying synchrony, or the unscripted coordinated interactions, in human relationships.

Feldman and her colleagues recorded and micro-analyzed babies and adults while they interacted—their gazes, sounds, and emotional expressions, along with their heart rates and hormones. When the interactions were synchronized, or had a coordinated, turn-taking quality, caregiver and infant heartbeats tracked each other within a one-second lag; that is, when one sped up, the other accelerated within a second. The more the pair was in synchrony, the more their levels of oxytocin (the love and bonding hormone) tracked, too. There was no difference between male and female caregivers, nor between male and female babies.

Feldman defines synchrony as the coordinated social interactions between people in which hormonal, physiological, and behavioral cues are exchanged. When interactions are synchronous, both participants’ brains activate the same areas and release the same hormones. In exchanges with minds that are still developing, the capability for positive interactions is transferred to the baby or child, supporting their growing ability to enjoy and thrive in relationships. Longitudinal studies have shown that this early synchrony in caregiver-baby relationships leads to a child having greater empathy, better self-regulation, and improved social skills later in life.

One of the best displays of synchrony can be seen in the still-face experiment. Babies and their mothers or fathers are seated facing each other, and at first, the adults are told to interact normally with their babies. In videos of this phase, we can see the playful give-and-take. Then the adult is asked to hold their face still, motionless and expressionless, like a mask. Instantly, the baby becomes visibly distressed. They turn their face away and back again, and they flail their arms, as if trying to draw the adult back into the connection. Some babies adopt a frozen attention in an attempt to lock in and control their caregiver with their eyes. Eventually, all the babies dissolve into helplessness, frustration, or fear. It isn’t until the adult re-engages and the rupture is repaired that the baby relaxes and comes back into relationship.

Research on older children and adults confirms that we suffer when our relationships are torn. Being rejected, excluded, or ostracized can activate the same neural pathways as physical pain, only social pain may be worse because it is relived, over and over, in a person’s mind. One study of children’s daily stresses, where their stress hormone cortisol was sampled twice a day, provided a peek beneath the surface of a rupture. When one nine-year-old girl was scolded, hit, and threatened by her caregiver for spilling a glass of water, the child’s cortisol levels were elevated for two days; four days later, she was sick with a fever and a cold. Prolonged stress also undermines the immune system.

Children who are bullied at school can develop physical symptoms like abdominal pain; headaches; and chest, back, and joint pain, along with emotional and interpersonal problems that can last a lifetime. Social isolation and loneliness raise health risks at a rate similar to smoking, and they triple mortality risk. One of the most well-documented examples of our physical connection is the “widowhood effect,” the increased likelihood of dying in the first three months after the loss of a beloved partner, especially of a “broken heart.”

Yet disconnections are a fact of life.

But it’s not realistic, or possible, or even healthy to expect that our relationships will be in synchrony all the time. Even babies disconnect, crawling away from their secure base to explore the world. School-age children try out new activities and grow new relationships with friends and teachers. Teens individuate from parents, striving to be psychologically independent while remaining connected to their parents. And adult children have full lives of their own.

Raising a family is about constantly renegotiating our connection amidst an ever-shifting balance of power with children. Life itself is dynamic, not static; we are constantly adapting to fluctuating circumstances. The alternative scenario would be a rigid, frozen, inflexible orientation that would obstruct our ability to get anything done, prevent our growth, and imperil our survival. It is unrealistic to think that our connections with family members and loved ones won’t be disturbed and disrupted. We are constantly navigating the ever-changing waters of closeness and distance, rupture and repair.

In fact, Ed Tronick, who created the Still-Face Experiment, together with colleague Andrew Gianino, calculated how often infants and caregivers are attuned to each other—and they found that it’s surprisingly little. Even in healthy, securely attached relationships, caregivers and babies are in sync only 30% of the time. The other 70%, they’re mismatched, out of synch, or making repairs and coming back together. Cheeringly, even babies work toward repairs with their gazes, smiles, gestures, protests, and calls.

These mismatches and repairs are critical, Tronick explains. They’re important for growing children’s self-regulation, coping, and resilience. It is through these interactional mismatches—in small, manageable doses—that babies, and later children, learn that the world does not track them perfectly. These small exposures to the micro-stress of unpleasant feelings, followed by the pleasant feelings that accompany the repair, are what give them manageable practice in keeping their boat afloat when the waters are choppy. Put another way, if a caregiver met all of their child’s needs perfectly, it would actually get in the way of the child’s development.

Life is a series of mismatches, miscommunications, and misattunements that are quickly repaired, says Tronick, and then again become miscoordinated and stressful, and again are repaired. This occurs thousands of times in a day, and millions of times over a year. Tronick compares the experience to training for a marathon. Runners don’t run marathons to train for a marathon, he writes:

They run a specific amount each day and week and increase the distance over the course of weeks and days. However, it is not until they actually run the marathon that they run the full distance. The earlier training leads to the development of the capacity to extend themselves to the full distance. The daily training in a sense developed their coping capacities such that they had the resilience to go the full distance. Of course, without the training had they tried to go the full—traumatic—distance they would have failed. (Tronick, 2006, p. 84)

As children grow, relationships are threaded with conflicts. Children have more conflicts with their friends than with non-friends, but with friends, they also use more strategies to preserve the relationship, like negotiation, problem-solving, and finding fair-minded solutions. Sibling conflict is legendary but also precarious, because while practice resolving conflicts with siblings can promote development, sibling aggression is also the most common form of family violence—something that needs more attention. Adults’ conflicts escalate when they become parents, but if handled well, the conflicts can serve to strengthen the relationship by finding a new balance and deepening understanding and intimacy after differences emerge.

If relationships are critical, yet interpersonal conflict is unavoidable—and even necessary—then the only way we can maintain important relationships is to get better at re-synchronizing them, and especially at tending to repairs when they rupture.

Repairing ruptures is essential.

“Repairing ruptures is the most essential thing in parenting,” says UCLA neuropsychiatrist Dan Siegel, director of the Mindsight Institute and author of several books on interpersonal neurobiology. When the relationship is positive, there is a trust and a belief in the other’s good intentions, and children easily restore from minor ruptures.

But if you “lose it,” as we all do, he says, it’s important to go back to the child, apologize, find out how it felt to them, and assure them you’ll do everything in your power to not repeat it.

photo credit: iStock: Fizkes

This can be tricky for adults. Apologizing to a child might feel beneath us, or we may fear that we’re giving away our power. We shouldn’t have to apologize to a child, because as adults we are always right, right? Of course not. But it’s easy to get stuck in a vertical power relationship to our child that makes backtracking hard. Vertical relationships are those moments in which we exert power over our children: when we direct and socialize them, train and teach them, monitor, set limits, and guide. Of course these are necessary parenting controls, particularly in situations involving safety, but they have to be in balance with more equitable, and even solicitous, power dynamics.

In a small Canadian study of how parents of four- to seven-year-old children strengthen, damage, and repair their relationships with their children, parents reported that it was their overuse of power and authority, and especially stonewalling (shutting children out, giving the silent treatment), that most harmed their relationships with their young children. Their relationships were strengthened, though, in more horizontal power dynamics like playing together, negotiating, sharing, collaborating, taking turns, compromising, having fun, and sharing in psychological intimacy. Parents repaired missteps and restored intimacy by expressing warmth and affection, talking about what happened, and/or apologizing.

photo credit: D. Divecha

The multifaceted nature of family relationships feels to me like a fabric in which the weaving is largely directed by the parents when children are young. But as children grow, parents increasingly yield the pattern to the young adults. Stitches can still be dropped and threads misaligned.

Prior to our visit, my daughter and I had a phone conversation. We shared our excitement about the rare chance to spend so much time together. Then we gingerly expressed our concerns.

“I’m afraid we’ll get on each other’s nerves,” I said.

“I’m afraid I’ll be cooking and cleaning the whole time,” she replied.

So we strategized about preventing these foibles. She made a spreadsheet of chores where everyone signed up for a turn cooking and cleaning, and we discussed the space needs that people would have for working and making phone calls.

Then I drew a breath and took a page from the science. “I think we have to expect that conflicts are going to happen,” I said. “It’s how we work through them that will matter. The love is in the repair.”

On our first night together, my daughter’s husband began dinner with an invitation for gratitude reflections. “The silver lining to this awful time,” he said, “is that we can be together. I’m so grateful for that.” And we went around the table and shared. It set a positive tone.

And yet, we had some bumps. There was a coup against the rigor of the chores spreadsheet. And I did flap my lips and divulged something my daughter thought I shouldn’t have. I was momentarily mortified, but I engaged in a couple rounds of apologies and repairs.

“Thank you,” she said simply. Then she smiled, teasing, “Don’t you know my love language is feisty?”

One hot afternoon, I came upon my son-in-law watering the flowers outside. I’d been on a walk, and my feet were sandy and dirty.

“Wait,” he said, stopping me. Then he showered water from the watering can onto my bare feet, and with his hands, gently rubbed them clean.

I was moved by this humble gesture and felt filled with appreciation for a good repair.

“Relationships shrink to the size of the field of repair,” says Rick Hanson, psychologist and author of several books on the neuroscience of wellbeing. “But a bid for a repair is one of the sweetest and most vulnerable and important kinds of communication that humans offer to each other,” he adds. “It says you value the relationship.”

* * * * *

How can we get better at repairing little and big ruptures in our families?

There are infinite varieties of repairs, and they can vary in a number of ways:

The age of the child. Infants need physical contact and the restoration of love and security. Older children need affection and more words. Teenagers may need more complex conversations.

Temperament and style. What is hurtful to one child may not faze another child. Or one child may need words, while another is not as verbal. Also, your style might not match the child’s, requiring you to stretch further.

Depth of the apology. Some glitches are little and may just need a check-in, but deeper wounds need more attention. A one-time apology may suffice, but some repairs need to be acknowledged frequently over time to really stitch that fabric back together. It’s often helpful to check in later to see if the amends are working. Keep the apology in proportion to the hurt. What’s important is not your judgment of how hurt someone should be, but the actual felt experience of the child’s hurt.

It helps to proactively tend the fabric of family relationships:

To weave a resilient fabric that will help hold you together, encourage trust in one another’s good intentions. Appreciate out loud, share gratitude reflections, and notice the good. If you’re unsure about a child’s motives, check their intentions behind their behaviors; don’t assume they were ill-intentioned.

Model respect and healthy boundaries, and take responsibility for your own feelings. Work to understand and heal from your own unresolved traumas, instead of blowing them across others.

Watch for tiny bids for repairs. Sometimes we have so much on our minds that we miss the look, gesture, or expression in a child that shows that we transgressed. Catching a misstep early can help.

Normalize requests like “I need a repair” or “Can we have a redo?” We need to let others know when the relationship has been harmed.

Bolster relationships with more equitable horizontal interactions: sharing, playing, negotiating, collaborating.

Spend “special time” with each child individually to create more space to deepen your one-to-one relationship. Let them control the agenda and decide how long you spend together.

When you’re annoyed by a family member’s behavior, try to frame your request for change in positive language; that is, say what you want them to do rather than what you don’t. Language like, “I have a request…” or “Would you be willing to…?” keeps the exchange more neutral and helps the recipient stay engaged rather than getting defensive.

Keep your own activation low.

If you think you might have stepped on someone’s toes, circle back to check. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Cultivate wise speech. Words—and silence—have weight. Consider how the other person might receive what you’re saying.

Adopt the mindset that conflicts are normal and just need some special tending. We will all make mistakes in any long-term relationship.

Model healthy repairs with people around you, so children normalize them and see their usefulness in real time. Children benefit when they watch adults resolve conflict constructively.

When it’s time to recalibrate, authentic repairs have some steps in common:

1. Acknowledge the offense.

“Acknowledging the wound is what gets the thorn out.”

First, try to understand the hurt you caused. It doesn’t matter if it was unintentional or what your reasons were. This is the time to turn off your own defense system and focus on understanding and naming the other person’s pain or anger.

Sometimes you need to find out more and check your understanding. Begin slowly: “Did I hurt you? Help me understand how.” This can be humbling and requires that we listen with an open heart. It also requires that we work to take the other person’s perspective.

Try not to undermine the apology by adding on any caveats like blaming the child for being sensitive or ill-behaved or deserving of what happened. Any attempt to gloss over, minimize, or dilute the wound is not an authentic repair. Children are “emotional Geiger counters” and have a keen sense for authenticity. Faking it or overwhelming them will not work.

A spiritual teacher reminded me of an old saying, “It is acknowledging the wound that gets the thorn out.” It’s what reconnects our humanity.

2. Express remorse.

Here, a sincere “I’m sorry” is sufficient.

Don’t add anything to it. One of the mistakes adults often make, according to therapist and author Harriet Lerner is to tack on a discipline component: “Don’t let it happen again,” or “Next time, you’re really going to get it.” This, says Lerner, is what prevents children from learning to use apologies themselves.

On the other hand, some adults—especially women—says Rick Hanson, can go overboard and be too effusive, too obsequious, or even too quick in their efforts to apologize. This can make the apology more about yourself than the person who was hurt. Or it could be a symptom of a need for one’s own boundary work.

There is no perfect correctness to an apology except that it be delivered in a way that acknowledges the wound and makes amends. And there can be different paths to that. Our family sometimes uses a jokey, “You were right, I was wrong, you were right, I was wrong, you were right, I was wrong,” to playfully acknowledge light transgressions. Some apologies are nonverbal: My father atoned for missing all of my childhood birthdays when he traveled 2000 miles to surprise me at my doorstep for an adult birthday. Words are not his strong suit, but his planning, effort, and showing up was the repair. A relative has apologized numerous times for a racist remark he made as a teenager about my multiracial family. Apologies can take on all kinds of tones and qualities.

3. Consider offering a brief explanation.

If you sense that the other person is open to listening, you can provide a brief explanation of your point of view, but use caution, as this can be a slippery slope. Feel into how much is enough. The focus of the apology is on the wounded person’s experience. If an explanation helps, fine, but it shouldn’t derail the intent. This is not the time to add in your own grievances—that’s a conversation for a different time.

4. Express your sincere intention to fix the situation and to prevent it from happening again.

With a child, especially, try to be concrete and actionable about how the same mistake can be prevented in the future. “I’m going to try really hard to…” and “Let’s check back in to see how it’s feeling...” can be a start.

Remember to forgive yourself, too. This is a tender process, we are all works in progress, and adults are still developing, too. I know I am.

* * * * *

For further exploration:

Rick Hanson, Ph.D. (2019) Being Well Podcast: Repairing Relationships.

Greater Good Science Center (2020) How to Apologize.

Andrew Newberg and Mark Robert Waldman (2012). Words Can Change Your Brain: 12 Conversation Strategies to Build Trust, Resolve Conflict, and Increase Intimacy.

The TikTok app is full of families having fun together, especially during the pandemic lockdown. Here are a few examples.

Harriet Lerner (2017). Why Won’t You Apologize: Healing Big Betrayals and Everyday Hurts.

Harriet Lerner and Brené Brown (2020). Podcast: I’m Sorry: How To Apologize & Why It Matters.

Fred Luskin (2002). Forgive for Good: A Proven Prescription for Health and Happiness.

Resmaa Menakem (2020). My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies.

The Gottman Institute: A Research-based Approach to Relationships